|

Orchid

News # 34

|

|

XIX WOC

|

|

|

Phalaenopsis

violacea and Phalaenopsis

bellina - the moral behind the story by Michel OOi |

|

During

the 11th World Orchid Conference, 1984 in Miami,

I wanted so much to talk on Phalaenopsis

violacea and was especially proud because

after blooming thousands of plants, I was able

to select a very special coloured variety and

breed enough seedlings; subsequently offering

for sales my blue Phalaenopsis violacea .

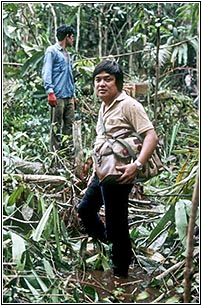

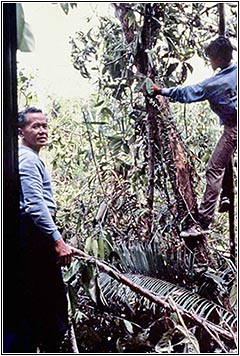

But the subject chosen for me to speak was about “Collecting Paphiopedilum of Malaysia.” – can you imagine my disappointment? I know, if given a chance to speak on this subject – “Collecting Paphiopedilum of Malaysia” again, I would be happy to share with you the many stories about my adventures and the habitats of Paphiopedilum sanderianum, Paphiopedilum volonteanum, the rediscovery of Paphiopedilum lawreancaenum and my discovery of Paphiopedilum ooii. I would have shown you the pleasure of vacationing in the Resort Islands of Langkawi, where Paphiopedilum niveum could be seen flowering by the thousands. Where you would have driven up the mountains and able to see Paphiopedilum callosum growing and flowering by the side of the road. Going to Lake Resorts where orchids are found on every tree. We can go fishing, bird watching and if you are lucky, you can even find your very own “islands of orchids”. Therefore, you can only imagine the thrill I experienced when I was invited to speak on Phalaenopsis violacea and Phalaenopsis bellina. Something I wanted to do so much at the World Orchid Conference in Miami 24 years ago. It has been THAT long that even this particular species was reclassified as two different species. It would definitely be easier to talk on this species 24 years ago because then it was just one species - Phalaenopsis violacea . Thanks to Eric Christenson, we now know that those from Peninsula Malaysia are Phalaenopsis violacea and those from Borneo are Phalaenopsis bellina. Now what about those from Sumatra Islands? Well, all that needed to be written and discussed on this orchid species has been documented. All that needed to be done for these two fascinating species had already been done. The progeny of these two phalaenopsis species, I believe has the most awards and the most numerous numbers of hybrids. For me, it started during the trip to visit Mrs. Irene Dobkin in 1972 with the purpose to see her collection of Phalaenopsis gigantea and her infamous Asconopsis Irene Dobkin; where below all the huge plants of Phalaenopsis gigantea, I saw a tiny little red flower that smelled so sweet. This fatal attraction got me a scolding from Mrs. Dobkin for not even knowing a species that came from somewhere near my home. I never did forget that day as it was the beginning of a long and fateful journey. Now 35 years later in my 6th generation of line breeding the Phalaenopsis bellina. I am ashamed to say that it was only two years ago, that I bred my first seedpod of a regular Phalaenopsis violacea . Back then, when I first started to collect Phalaenopsis violacea , it never crossed my mind to consider the necessity of making seedpods for this species and the need for propagating this species in my laboratory. With the habitats gone now and this species almost extinct in the wild, I am glad that I will soon have seedlings bred from selected jungle-collected plants. As far as I know, there is only one place in Peninsula Malaysia that this species could be found. It is a well known fact that the last known habitat where one can find Phalaenopsis violacea is in the State of Perak in Malaysia. This forest of which most of it was a swampland of about 5,000 acres is in fact a Phalaenopsis violacea paradise for me. It was the happiest ‘playground’ for me – a naughty young boy 35 years ago and now still the same - but maybe a bit older. The forest is about twelve kilometres from the town of Langkap which is located about 100 kilometres from the town of Ipoh. The last weekend of every month would be ‘playtime’ for me and my collector friends to go looking for these sweet smelling flowers. And believe me, we normally come out with hundreds of these species – most of the plants collected are flowering and many with seedpods. All I can say is that the only habitat of Phalaenopsis violacea is now gone.

For these 5,000 acres of swamp is now a new township with proper roads with proper infrastructure, with schools, hospitals, factories, shops and a healthy and thriving oil palm industry. If only I knew what I was doing then was actually saving these plants from extinction, I would have saved them all. I was back there three years ago and was truly devastated losing a place which I had so much fun and fond memories. But looking at the children playing, going to school, people having coffee with their friends, women going shopping with their babies, perhaps it was selfish of me to only think of the good times that this place has given me. I have attended many conferences and even argued with my fellow dedicated conservationists. I agreed with them that the destruction of the orchid habitat is a horrendous thing; for this is the biggest treat to the extinction of a species. The destruction of natural habitats of orchids following development is as sure as night following day and nothing is going to stop it, nothing that we, as orchid lovers, can say or do to stop this natural phenomenon of development and advancement. Logging, mineral development, energy projects are all big money, and all these are made possible only from the sacrifice of our jungles. Phalaenopsis violacea of Malaysia is the perfect example of a very unfortunate victim in the face of development and advancement. Even with all the endless committees around the world, with the names of important people on them, we have spoken, expressed our feeling and strong sentiments on conservation, we have made impassioned plea with our governments, but sadly, I think we have achieved very little. I remember very well the argument I had many years ago during a conference with the late Mrs. Andree Millar from Papua New Guinea. She asked me why I can not leave the Phalaenopsis violacea alone. I simply told her that I believe in looking for the best to breed for more. My reply certainly didn’t help with our relationship. It was only after about fifteen years later, during another international orchid dinner party, that I had the most wonderful surprise. Mrs. Andree Millar actually came over to my table to say hello and with a smile on her face, told me that what I am doing is also helping in conservation. I could not help but smiled back, and we became best of friends. What I have done with Phalaenopsis violacea might not be the best and most scientific way in saving a species but I sincerely think it helped, in whatever small way. What we did was to collect as many as we could manage; grow them, flower them, selecting desirable qualities and start breeding more of this wonderful Phalaenopsis violacea or any other species. By selection of more desirable quality in a species, the seedlings produced are definitely prettier then plants collected from the jungle. This not only makes a species more desirable, you are actually taking the pressure away from plants being collected from the wild. Now for the bigger question. Is there something we can learn from these two species? Here we have two species that showed us what could happen if we are not careful about our intentions and the directions we take in our efforts of conservations of a species. |

Phalaenopsis bellina |

Unlike Phalaenopsis

violacea , where her habitat is only about

5,000 acres and a few miles from a village;

the habitat of Phalaenopsis bellina is

our planet’s third largest island – Borneo,

with an area of 743330 sq. kilometre or 287000

sq. miles.

During those early years, I did not care to breed more of the Phalaenopsis violacea , for the simple reason that there were plenty and Phalaenopsis violacea is definitely not as pretty compared to Phalaenopsis bellina. Given a choice, orchid hobbyists and nurserymen would normally prefer having the Phalaenopsis bellina. And there are too many species in the wild suffering the same fate as the of Phalaenopsis violacea simply because they have lesser or no commercial value. I do not see the possibility of species such as Paphiopedilum sanderianum, Paphiopedilum rothschildianum, Phalaenopsis bellina or other such pretty and valuable species being lost to extinction. What I am more concerned is what will happen to the little guys, which, perhaps, are not as “pretty” and preferred as the others and flower only for a few hours? Are they not worth saving? |

|

First,

it is a virgin jungle, and then we need to invade

into our jungles for natural resources like timber

and minerals. Later, land for agriculture, followed

by settlements and new villages. Even their mountain

habitats are not spared. Now, many countries in

Asia are boosting luxurious mountain resorts with

golf courses, not to mention huge areas being cleared

for the cultivation of tea.

Maybe we can discourage tourism and we can try to stop drinking tea! This might help save the orchid species? Discovered in the 1800’s, these two species not only has given us such great pleasures of growing, flowering and getting them awarded. We have also bred some of the most beautiful orchid hybrids. Now two hundred years later, shouldn’t we now look seriously what these two species are trying to tell us? For the other not so desirable species, there doesn’t seem to be a solution. Many of these “little guys” are doomed. Can their silent plea for survival be heard? Isn’t this sad? Fotos: Michel OOi e Charles Marden Ficth |

|

É

expressamente proibido qualquer tipo de uso, de qualquer material

deste site (textos, fotos, lay-out e outros), sem a expressa autorização

de seus autores sob pena de ação judicial. Qualquer

solicitação ou informação pelo e-mai:bo@sergioaraujo.com

|